Comic Book Eras are Pointless

This is the text version of this video.

Usually the story of American comics goes something like this:

In 1938 Superman was invented. This started off the Golden Age of comics when we had superhero stories that were kinda serious, but also kinda silly. Batman used guns and Captain America punched Hitler.

In 1954 a mean man named Frederic Wertham said comics are bad so they became silly and Batman started to wear all sorts of weird costumes and turn into a baby. But at least superhero comics were popular again so this was the Silver Age.

By the 70s comics started to get serious again because Gwen Stacy died and Speedy became a heroin addict. Since the paper is all yellow, the Bronze Age title was coined.

The best years were 1985–1986 because the whole DC universe died then, we saw a blue penis and Batman got old. And because it was good, we call it the Modern Age.

Then comics became too dark, there were only pouches and lots of teeth and heroes dying. Hence the 90s were the dark age.

After that, things turned normal again and it was the Modern Age again or it became weird so it was the Prismatic age. Or something like that.

There are some problems with this way of looking at comics. First, the gaps. And, at least for now, i’m not going to be pedantic about it and complain that looking at history this way we ignore seminal comic book strips like Freudian Boy, Surrealist Kat, Water Nazi Adventures and White Boy or early auto-bio underground comics like Binky Brown.

There are gaps, strange overlaps and fuzzy areas even in the way we conceive of commercial, newsstand distributed slash Direct Market comics. The 50s, for example is such a period. Definitely not the Golden age, but not yet the Silver Age. The late 80s are another one, since all the “Modern Age” comics mentioned come in a very narrow time-frame, but the “Dark Age” trademarks don’t come into play until the early 90s. We can say that from the time DC started to bring back The Multiverse we’re reaching the Prismatic Age, as it was coined by The Mindless Ones’ Duncan Falconer, but that still leaves us with the late-90s and early to mid aughts. When the gaps are larger than some of the ages, can they be called ages at all? To make things even more confusing, we notice that almost all the demarcations are much more dependent on DC comics, than on Marvel.

Then there’s the lived experience of people which happens to contradict these characterizations or at least brings a lot more nuance to them. When you ask David Lloyd about favorite comics from his youth he’ll either say that time forgot them or mention the short stories from Ditko’s Amazing Adult Fantasy that aren’t The Amazing Spider-Man. When you ask Howard Chaykin what he read when he was a teenager he’ll name Angel and the Ape, Enemy Ace and Bat Lash. This especially happens around the 90s, since that wasn’t all that long ago and people remember what they read. There are countless discussions on internet forums, subreddits, or comments on YT videos about how the 90s weren’t that bad or monolithic.

So, if the periods aren’t as contiguous and well defined, nor do they fit their descriptions as tightly as the story goes, why do we have them?

By the sixties, superhero comics were becoming once again popular. The reinvention of brands like The Flash and Green Lantern with the popularity of The Batman TV show, spurred an increase in nostalgia for some older superhero comics, and, since Netflix wasn’t around yet and people didn’t have anything better to do, they started to collect the comics they got nudged into remembering.

This, in turn, created a market for the resale of older comics and an entire ecosystem of fanzines and adzines people used to advertise the comics they are willing to buy and sale to fill their collections. Which means that the earliest literature about comics was as much criticism and historiography as it was ye old-timey E-Bay, if not moreso.

This is the ecosystem in which the terms developed and to this day the people who use them the most are the collectors. At first there were competing terms, like The First and Second Heroic ages, especially since some people remembered the Golden Age as being about the strips from the papers, but eventually the Golden/Silver/Bronze names won and stuck.

If we look at comics not through the prism of a genre’s evolution, artistic and narrative devices, styles or subjects, but through the lense of what gives a collectible its value, using these terms makes a lot more sense.

Intact superhero comics from the 40s are extremely hard to find. A lot of time passed, people weren’t collecting and caring for them at that time, they would’ve been pulped or burned and they hold the first appearances of some of the most important characters in modern pop-culture, like Superman or Batman. They’re the golden standard of scarcity, cultural significance and arbitrary fixation.

Genre comics from the 50s are scarce and valuable, but don’t have the same force pulling them, in the way superheroes have.

Superhero comics from the late 50s and sixties still have many first appearances, if not of important characters like Barry Allen and Hal Jordan, then at least of secondary and ancillary characters that have turned big or whose profile will be raised, at least temporarily, by some movie or T.V. show. And at least until 1964, first-print copies in top shape remain quite rare.

By the 70s the wave of important new characters eventually stopped and enough people got into collecting. There are still some notable new appearances, some notable events, and comics were still mostly bought to be read. So it’s not like you’ll stumble at every comic con on a mint issue of Green Lantern / Green Arrow #85.

In the 80s, most of the 90s and the current era the direct market made out of comics a collectors game. Non returnable comics are sold to stores and kept in decent conditions. Comic companies try to manufacture valuable collectible comics with variant covers, but with modest success. Which is why these periods aren’t that interesting. There are enough of those comics around, kept in more than proper shape that they would be relevant only to someone who wants to read those stories and maybe capitalise slightly on temporary increases in interest brought by Hollywood.

The mid-90s was when this balance was broken and the comics companies printed so many comics, with so little collectible value, abused the marked in such a way that at some points just keeping those comics in a warehouse costed more than just giving them away. Indeed, a dark age for collecting.

And since for so long a time, the comics history was told by collectors, mostly for collectors, this is how we all ended up looking at comics. It’s telling that the first two periodicals about the medium were the Overstreet Comic Book Price Guide and the Comics Buyer’s Guide, appearing seven, respectively six years before The Comics Journal. This is one of the reasons why there isn’t a unified telling of the history of comics and comics strips. And because Overstreet thought underground comics were a poor investment we don’t really mention them when we tell the story of comics.

I don’t begrudge the collectors. The history we have, we have it through them. The comics we have, through which we can map a broader, richer history, we have from them. In their own way and for their own reasons, they cared for those comics. And now, when we think of comics not as objects, we should be able to trace a different chronology. But there’s another a reason why we so intuitively buy into this view of history, why we accept it and cling to it. Why we think so much about the dark age, for example, when even the collectors recognize some value there and paper over it by dubbing the first modern age and the early 90s as the copper age. Of course it’s the copper age. That reason is the superhero comics themselves.

By the 80s, there came a generation of writers who grew up reading those publications, those fanzines and guides and their project was, intentionally or not, to canonize the comic book ages, by placing themselves at the precipice of a new era. Many of them were British, so they must have grown only with a limited selection of the comics actually published or a distorted timeframe.

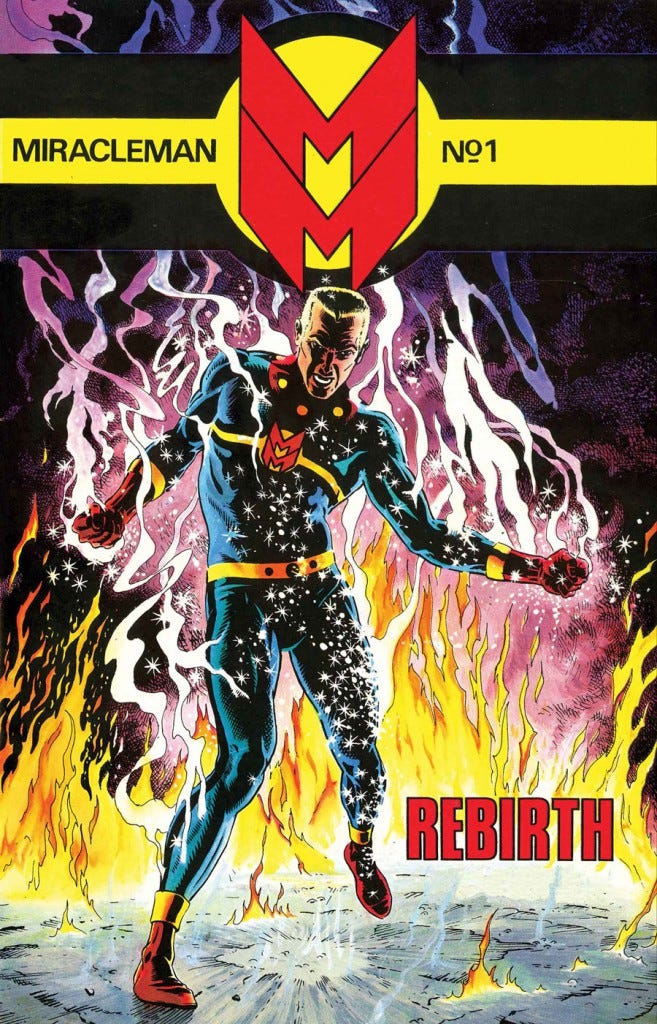

Alan Moore’s Miracleman is the first and probably one of the strongest example of one such comic. The american reprint opens up with a sequence greatly indebted to the Golden Age Captain Marvel stories and Mick Anglo’s Marvelman’s comics. Later in the series. when Miraclewoman retels her story, there are references to Silver Age Supergirl comics. The Miracleman comic is, obviously, beyond such childish adventures. It’s more mature, thoughtful and daring. The Neil Gaiman and Mark Buckingham sequel series continues this approach, labeling its story arcs according to the comic book eras and making some efforts to reflect them, for example by having a Galactus-type being appear in the first issue of the Silver Age arc.

Alex Ross contributed to this project immensely. Marvels is a four-issue miniseries written by Kurt Busiek and painted by Ross in which the fictional history of Marvel comics is retold through the lense of Phil Sheldon’s humanizing camera. The four issues are mapped out pretty closely on The Golden Age, with the first Human Torch, then early Silver Age with the advent of a new crop of heroes, the apocalyptic events from the late Silver Age and the grief and tragedy that was brought upon in the Bronze Age. Then came Kingdom Come, another four-issue miniseries, this time written by Mark Waid and published by DC, which positioned the old, traditional heroes against violent and gimmicky characters, inspired by those of the mid-90s. Ross continued this project of rewriting comics history together with Busiek and Brent Anderson in Astro City, creating comics about idealised analogues of classical comics characters. They too used arcs like The Silver Agent or The Dark Age to comment on the comic book eras.

I don’t want to make it sound like Ross was the prime moving force in this. There was a convergence of purpose. Mark Waid, again, wrote a miniseries called Justice League: Year One that retold the origin of the Justice League in a much more congruos way with the official historiography, whereas the original Brave and the Bold stories were mostly individual stories that somehow met at the end.

James Robinson received the unthankful job of making the Golden Age characters fit into the DC universe. This was hard, because many of them were acquired in time, over decades and weren’t actually part of what would become the DC universe. But he got the job done with miniseries like the aptly titled The Golden Age and long-running series like Starman or Justice Society of America.

Probably the most obvious comic as historiography is Grant Morrison and Frank Quitely’s Flex Mentallo. The first three issues not only reference covers, events and characters from The Golden Age, Silver Age and Dark Age respectively, while the last one positioned itself as a sort of synthesis and fulfillment of the superhero form, but the series as whole can only be understood when read through this perspective. It is personal history told as that specific history of superhero comics.

Marvel, or rather Timely, had their own Golden Age comics and characters, their own modern age, dark and adult stories, but they wouldn’t fit the history as well. So in 2000, Paul Jenkins, with Rick Veitch and Jae Lae created the Sentry at Marvel, a Superman-type character. It fictional history of the story he actually was one of the first superheroes, just that he who was forgotten by everyone, in order to save the from his evil self, The Void. During the course of the story, Robert Reynolds remembers events from his life as the Sentry, represented by panels and covers drawn in the style of various eras. Interestingly, some of them callback much more to DC’s history. The Sentry is the triumph of a narrative about comics that collectors started telling themselves in the 70s. Such a strong and attractive story that it ended up re-writing the fictional course of Marvel comics.

It’s easy to be tempted by clear tales of linear progression, with some ups and downs for a bit of excitement. They make sense, they can be contained in a thought, in an image. You get a sense of how things are and ought to be, without actually knowing how they were. Doing so means shaving off edges, erasing parts of it and, when the world itself doesn’t conform to this idea, it seems easier to change the world itself and invent history, rather than to let the story unravel. With such a story in mind it can be really tempting to make it about yourself, to place yourself as its culmination. But that is unjust to the people who read these comics and cared for them and especially to the people who made them. Not telling their story because it would make yours less compelling is an act of selfishness. And don’t forget, when time will come for your own story to be told, somebody might think that it stands in the way of theirs and will let time swallow it whole.